Formula One’s paymaster, Liberty Media, may have thrust the sport deep into its American heartland—there are now three grand prix in the US—but it’s Nascar that continues to build its TV audience there against a slight decline for the “open wheel” F1 and IndyCar championships.

European race fans are famously sniffy about stock car racing, but there’s something about an ostensibly low-tech, normally-aspirated pushrod V8—with a capacity of 358 cubic inches (5.8 liters) and a 670-hp output—charging round an oval that reaches the parts other race series don’t. Or have perhaps given up on.

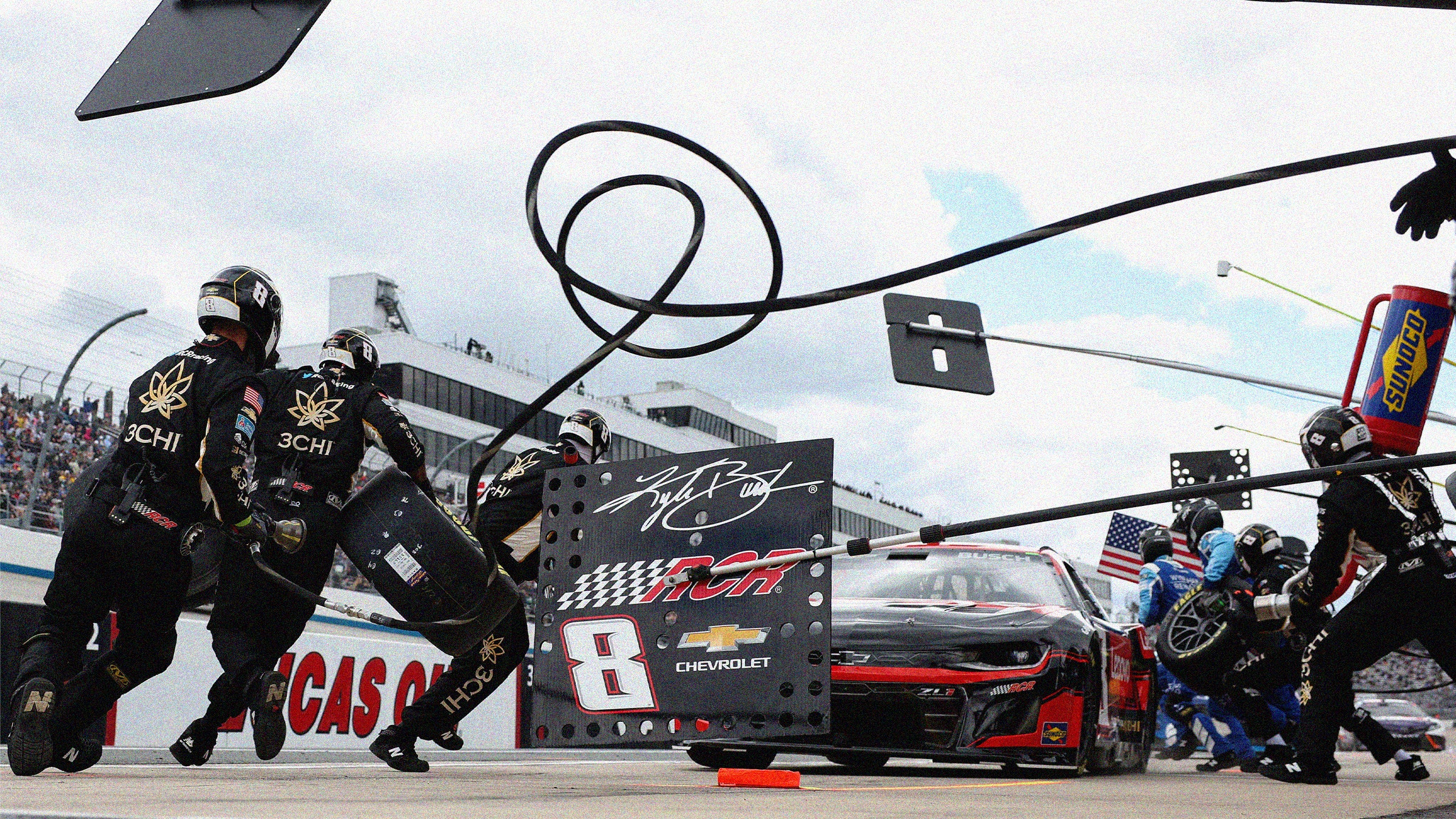

Not that the Nascar grid isn’t trying to gain a technological advantage every which way it can. Lenovo is working with one of the series’ biggest names, Richard Childress Racing, to help finesse its pit stops during a race—and there are lots of them in the Nascar Cup Series, anywhere between five and 12 depending on the circuit and what’s happening ontrack. In particular, the company is using AI to gain real-time insights into refueling.

Fuel mileage is obviously a critical part of any Nascar race, almost an art in itself—in addition to being a source of drama and jeopardy. (NB: Refueling has been banned in F1 since 2010 for cost and safety reasons.) The cars themselves aren’t fitted with fuel gauges in the cockpit, so it’s down to the teams’ strategists to constantly monitor the amount that goes in during a pit stop and the rate at which it’s consumed.

As with any other use case, fuel consumption depends on a number of variables, including the length and configuration of the track and the speeds the cars are running at. There are a number of “cautions” during a race, at which time the cars will typically use half as much fuel.

In Nascar, the drivers also “draft,” a technique that enables them to maintain speed in the pack without using full throttle. Less fuel consumed means fewer pit stops, and when they do pit they take on a smaller amount. On average, a Nascar Cup series car—not the most energy efficient device—will use 100 gallons (380 liters) of fuel in a race.

Lighter Is Always Faster

It’s not an exact science, but the aim of Lenovo’s AI team is to make it as close to one as possible. If RCR could measure the amount of time the fuel cans were connected to its cars, it figured, then the team could calculate more precisely the quantity of fuel delivered.

That was the brief. Lenovo’s response was to devise a system that used in-car transponders and a camera mounted above RCR’s pitbox to identify when a car has entered the box and begin a real-time videofeed.

Bob Sorokanich

“An AI engine looks at each frame and classifies whether the fuel can is plugged or unplugged,” Lenovo AI data scientist Sachin Wani explains. “We’re working at 30 frames per second, so the information is accurate to within about 0.03 seconds. Prior to this, the fuel man knew that he had to pump in about seven seconds worth of fuel—without any devices to help because of safety concerns.”

“So, basically it came down to mental calculations, which meant that seven seconds could become eight or nine. Or worse still, five or six. That obviously messes up the strategy, and creates a situation where they’ve short-fueled and need to make another pit stop,” says Wani.