Demis Hassabis didn’t know he was getting the Nobel Prize in chemistry from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences until his wife started being bombarded with calls from a Swedish number on Skype.

“She would put it down several times, and then they kept persisting,” Hassabis said today in a press conference convened to celebrate the awarding of the prize, alongside John Jumper, his colleague at Google DeepMind. “Then I think she realized it was a Swedish number, and they asked for my number.”

That he won the prize—the most prestigious in science—may not have been all that much of a shock: A day earlier, Geoffrey Hinton, often called one of the “godfathers of AI,” and Princeton University’s John Hopfield were awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for their work on machine learning. “Obviously the committee decided to kind of make a statement, I guess, when having the two together,” said Hassabis in a press conference organized after his win.

In case it wasn’t clear: AI is here, and it’s now possible to win a Nobel Prize by studying it and contributing to other fields—whether physics in the case of Hinton and Hopfield or chemistry in the case of Hassabis and Jumper, who won alongside David Baker, a University of Washington genome scientist.

“It’s no doubt a huge ‘AI in science’ moment,” says Eleanor Drage, senior research fellow at the University of Cambridge’s Leverhulme Center for the Future of Intelligence. “Going by highly accomplished and illustrious computer scientists winning a chemistry prize and a physics prize, we’re all bracing for who will be awarded a peace prize,” she says, explaining that colleagues in her office were joking about xAI owner Elon Musk being tipped for that award.

Drage calls the awarding of physics and chemistry prizes to AI researchers “a major polemic, not only within those disciplines, but looking in from the outside.” She suggests the awards could be for one of two reasons: either a notable shift in disciplinary boundaries enabled by the ubiquity of AI in academic research, or because “we’re so obsessed with computer scientists that we’re willing to slot them in anywhere.”

She isn’t sure which route this week’s decisions signify. But she and others are sure that it’ll make a meaningful difference to the future of research.

“Winning a Nobel by using AI may be a ship that’s sailed, but it will influence research directions,” says Matt Hodgkinson, an independent scientific research integrity specialist and former research integrity manager at the UK Research Integrity Office. The question is whether it’ll influence them in the right way.

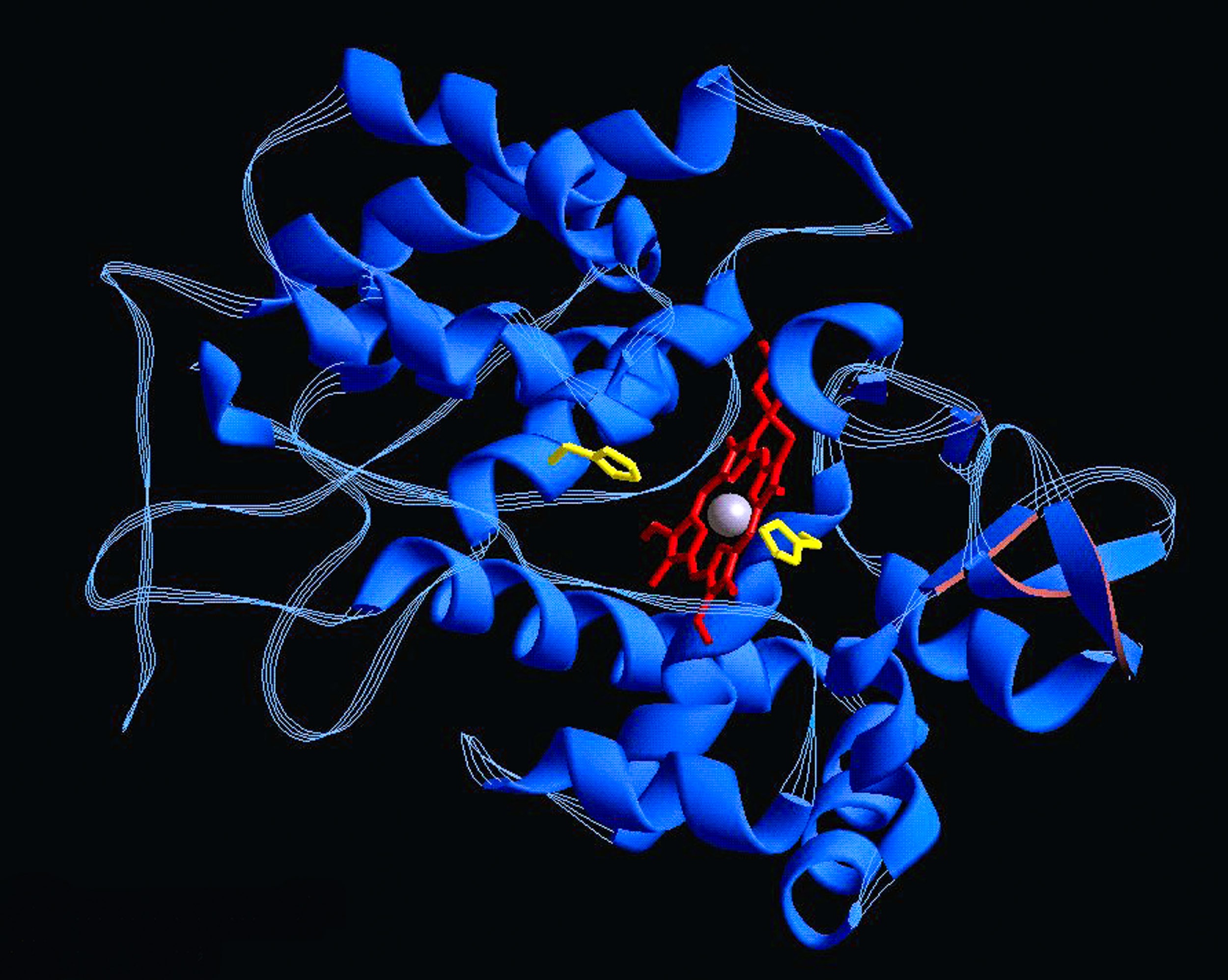

Baker, one of this year’s winners of the Nobel Prize for chemistry, has long been one of the leading researchers in the use of AI for protein-structure prediction. He had been laboring away for decades at the problem, making incremental gains, recognizing that the well-defined problem and format of protein structure made it a useful test bed for AI algorithms. This wasn’t a fly-by-night success story—Baker has published more than 600 papers in his career—and neither was AlphaFold2, the Google DeepMind project that was awarded the prize by the committee.