Jay fell in love with math at boarding school after a supportive physics teacher introduced him to the joy of complex calculus. He went on to study physics and math in college, hoping to one day similarly pass on what he’d learned to a new generation. That chance came in October 2022, when 25-year-old Jay answered a job listing seeking a math expert to grade equations through an online platform. But he would not be inspiring budding young mathematicians like his past self. He would instead be training an artificial intelligence system that may eventually make his expertise obsolete.

According to Jay, who asked to use a pseudonym to protect his privacy, the system he was schooling had been built by a company soon to be a household name: OpenAI. His job was to act as an expert guide for the company’s large language model—a machine-learning system that can convey information in a conversational format, like a chatbot—as it tried to improve its math. From his home in Portugal, he would tell the model if it was taking the right steps to solve math problems, adding thumbs up or thumbs down emojis to AI-generated answers, and sometimes writing out explanations about why the AI had gone wrong.

Jay says he knew he was training algorithms for the company overseen by Sam Altman because he was invited to join the OpenAI workspace in Slack. A screenshot he shared with WIRED shows he was part of a group, called “math trainers,” that was set up by the OpenAI researcher Yuri Burda. But Jay was not working directly for the famous AI company. Instead he was being paid by one of the world’s biggest data labor platforms, called Remotasks, a subsidiary of US startup Scale AI, which was valued at over $7 billion back in 2021 and counts OpenAI, Meta, Microsoft, and the US Army among its clients.

Scale AI works closely with its clients to provide and curate the training data they need to build up the AI models behind self-driving cars or large language models. Often, that data ultimately derives from people contracted to Remotasks—which has, according to its website, signed up hundreds of thousands of workers since it launched in 2017. Much of that workforce has been concentrated in countries that offer relatively cheap labor, like the Philippines, where Remotasks says its recruits mostly train computer vision for autonomous vehicles, helping self-driving cars recognize the shapes around them. But in the past year, the company claims the geography of Remotasks’ workers has shifted to the United States and Europe, as it searches for white-collar skills and language specialists to train large language models—fueling concern that these people are essentially training themselves out of a job.

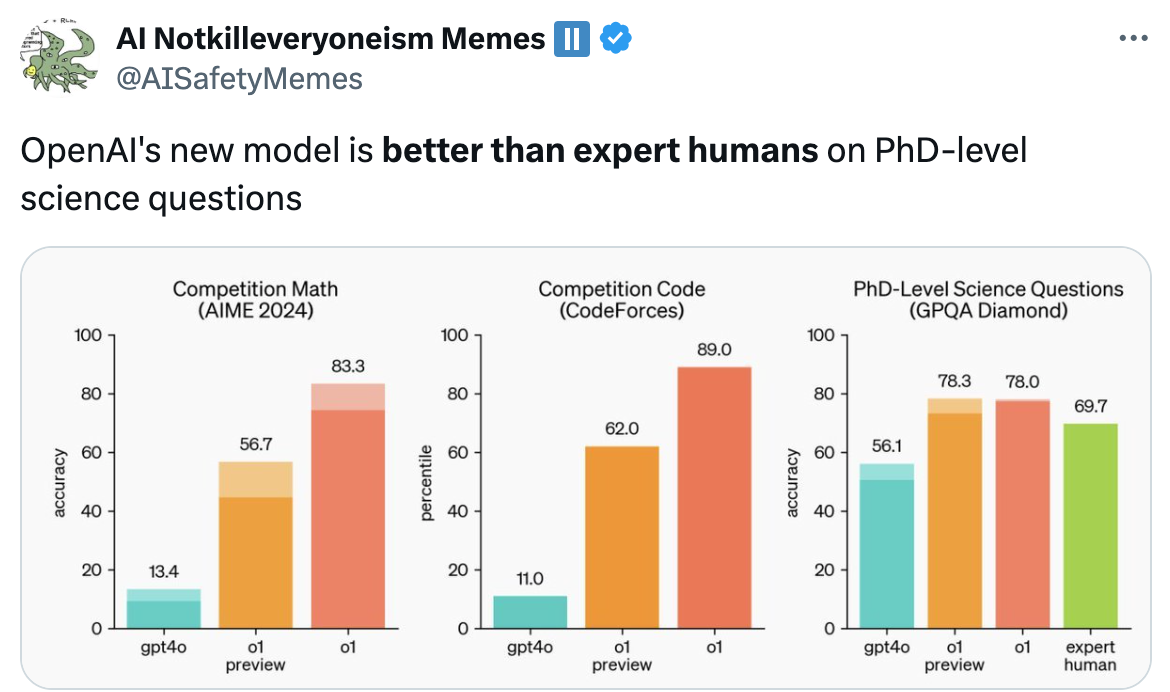

Jay is thoughtful about his role in the future of work. “It’s true,” he says. “I am passing on knowledge that I have and that the machine does not have.” He’s aware that AI models still struggle to replicate the ingenuity with which humans solve complex math problems. But he’s hoping the work he did will help create AI that can benefit, not replace, him—envisioning a future where he could practice algebra or calculus with a chatbot who can match his level. “That’s kind of what I was picturing, when I started training these.”

Willow Primack, VP of data operations at Scale AI, says that Remotasks and others are turning to subject matter experts for data labor in response to the major shift in the applications of AI systems, as these systems start to produce knowledge and content. As the tech industry has rushed to embrace generative AI over the past year and applied it to more sophisticated tasks, data providers have needed a new intake of contractors capable of what Primack calls “expert fact-checking.”